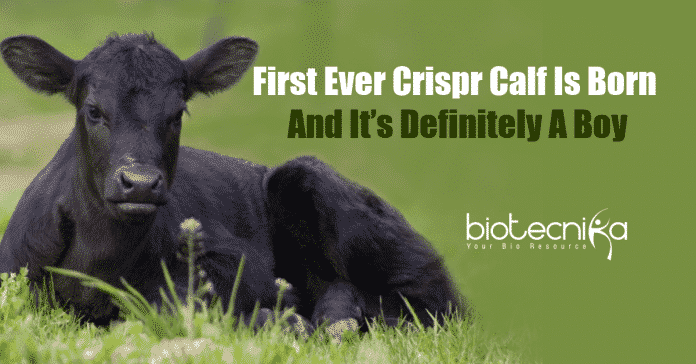

First Ever Crispr Calf Is Born And It’s Definitely A Boy

A Crispr male Calf Is Born. The calf bone was late. His due day was March 30, which had gone. Initially, one of the researchers – Alison Van Eenennaam noted that male calves tend to arrive a day or two delayed. As the week endured, the animal geneticist reminded herself that gene-edited embryos – like the one that had been growing inside Cow 3113 for the past 9 months can take a little bit longer to signal to their surrogate mothers that they’re ready to be born. However, next week she called the veterinarian and it was time to induce labor.

Almost after 5 years of research, at least half a million dollars, loads of failed pregnancies, and plenty of clinical obstacles, Van Eenennaam’s pioneering effort to develop a line of Crispr ‘d cattle tailored to the demands of the beef industry all came down to this one calf.

Jet black calf of 110 pounds with an ankle-grazing splash of white above his rear hooves was born on that afternoon – The first ever Crispr calf. The calf was extracted from Cow 3113 using chains by the veterinarians. However

, he was alive and breathing when he was lowered onto the straw-covered barnyard.

The black calf – big, strong, and healthy wasn’t exactly what the scientists had intended to develop. A detailed study at his DNA would certainly expose just exactly how unpredictable Crispr gene editing can be, as well as how much more scientists still need to discover before the technology can end up being a routine method for animal reproduction.

She had focused on cattle and a gene called SRY – a long stretch on the Y chromosome that develop male characteristics by instructing mammalian embryos. There’s an equivalent chance that cows (as well as humans) will give birth to male (XY) or female (XX) offspring when naturally bred. However, Eenennaam can alter the probabilities for producing an all-male herd. Animals with the SRY gene, even the animals that were genetically XX would be physiologically male if she could use Crispr to add a copy of SRY onto the X chromosome of bovine embryos. Eenennaam wanted to check this hypothesis, in any case.

The beef industry prefers bigger and meatier cattle, more males imply more money. Farmers could produce the same quantity of meat with fewer animals – possibly reducing the sector’s planet-warming emissions, due to the fact that male calves gain weight much more effectively than female calves.

The experiment required inserting a large piece of DNA into the bovine embryos. Only two such edits using Crispr had been in cow cells, and never in embryos, but still, they got a five-year grant worth 500,000 dollars from the US Department of Agriculture.

The very first step was trying to get Crispr to make the desired edits in bovine embryos – which targets a specific location in the genome and slice through the DNA’s double helix backbone. And it depends on the cell’s own repair mechanism to stitch the ruptured DNA. If you want to add new bits of genetic code between those loose ends, the technique is sliding the cell “template DNA” – in this instance a copy of the SRY gene – together with the Crispr.

This technique does not work much for single-cell embryos but works best in cells that are proactively dividing.

So they began again with an older as well as much less preferred technique – editing bovine cells and then cloning their DNA right into eggs. Owen added a gene for a green fluorescent protein, or GFP, in addition to the SRY gene, to make the process much easier. This GFP helps to visualize which cells had successfully inserted the genetic code for maleness onto the chromosome X. But, later they observed something strange, the cells that did incorporate the new DNA, the ones that glowed, all stoped dividing – the gene-editing had actually apprehended their growth.

Both the researchers consulted with breeders as well as veterinarians regarding what they were doing wrong. They thought that the researchers had damaged the embryos in the lab – possibly during the biopsy to sequence it and determine if the gene editing is successful.

They both attempted one last time, moving the SRY genetics into around 200 embryos, along with the glowing gene. Considering that it was their final shot, they decided to make the edit not on the X chromosome, as they had actually been trying to do, yet on chromosome 17 – a reputable safe harbor site. Out of 200, only 22 embryos survived this procedure, and of those, 9 glowed under UV, and however, only 1 of them was bright green. All the embryos were transferred into would-be surrogate heifers after a month, that bright green one was the only pregnancy that was successful.

Ultrasound suggested that Cosmo was a male and when he was born upon April 7, after making sure the calf was breathing, the second thing the vet checked was if it is a male.

Studying Cosmo’s DNA is detailed was required to understand if he had those male parts because of Crispr. The researchers collected blood samples of the calf for testing, and the PCR gel electrophoresis revealed the band appeared right where expected.

According to the test, the Cosmo was XY, indicating along with the SRY gene that Owen had Crispr ‘d onto his 17th chromosome, he had inherited a copy of SRY from his biological bull-dad.

The scan of Cosmo’s DNA showed a piece of genetic code that didn’t come from a cow or a jellyfish, but from a bacteria. Cosmo’s repair enzymes had grabbed the plasmid along with the SRY gene after Crispr had made its cuts and pasted the whole thing into his genome.

Any type of proof that the mutations harm the animals were not seen in any studies carried out mice with added copies of SRY, though it can create sterility in XX individuals.

The researchers wish to research whether those copies are sufficient to flip on the developing programming for making chromosomally female animals look and act (as well as gain weight) just like males.

First Ever Crispr Calf Is Born And It’s Definitely A Boy

Author: Sruthi S