Past Exposures Influence Immune Response to Pediatric Respiratory Infections

Acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) are the leading worldwide cause of death in early childhood and are responsible for 75% of acute illnesses in young children.

Viral infections are the primary etiology of most ARTIs. Influenza virus alone results in 50,000–430,000 hospitalizations and 3,000–49,000 deaths annually in the US. There have been detailed studies of immune responses in the setting of influenza vaccination and challenge. However, our understanding of the variation in outcome after natural infection and in the host factors and gene circuits underlying diverse clinical responses remains incomplete.

Host factors, including obesity, age, asthma status, and sex, may shape the inflammatory response and clinical outcome during ARTIs. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that such host factors can also influence adaptive immunity, including T cell responses.

But now a study at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania implicates a suite of genes expressed by early-response cells shaped by factors such as age and previous exposures to viruses.

“The notion that an individual’s capacity to combat the flu depends on what they have been exposed to in the past, especially early in life, has been gaining momentum,” said senior

author E. John Wherry, PhD, a professor of Microbiology and director of the Institute for Immunology at Penn. Wherry and Sarah E. Henrickson, MD, PhD, an instructor in the Allergy-Immunology division at CHOP, published their findings in Cell Reports this week.

“This study started during the 2009 H1N1 flu epidemic to find out how host responses change with different viral infections,” said lead author Henrickson, who began this work as a CHOP clinical fellow and postdoctoral fellow in Wherry’s lab.

“Children generally have a less complex infectious history and less co-occurring conditions than adult patients,” she said. “As a result we can more easily assess the immune response to an acute infection and test how immune history shapes responses to the new infection.”

CD8 T cells prepare the body for fighting foreign viruses by altering their own gene expression after sensing the alarm signals raised by cells in the lungs in response to acute respiratory tract pathogens. Previous studies elsewhere had investigated influenza responses broadly, but she wanted to focus on changes in CD8 T cells.

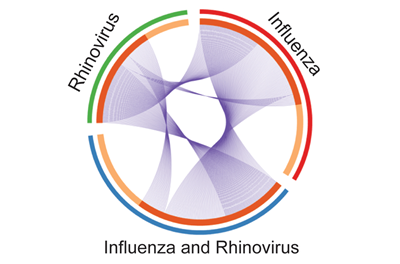

In this study, the CD8 T cell gene expression in acutely ill pediatric patients with influenza-like illness was distinct from patients with other viral pathogens, such as rhinovirus. In general, the “genomic circuitry” of a cell – clusters of genes akin to electrical circuits that affect each other’s expression – varies according to the type of pathogen.

The team analysed blood samples from 29 children who came to the CHOP emergency department with flu symptoms, the team found that different viruses elicit different immune responses – specifically, different patterns of genomic circuitry in CD8 T cells.

The team found that differences in severity of ARTI, asthma, sex, and age also influence the immune response in an individual child.

They noticed that the younger children’s CD8 T cell gene circuitry was different from older children’s, which correlated to whether the younger child was exposed to the flu virus or not at an earlier age. Younger children with antibodies to a flu virus (evidence of previous exposure) had a gene expression pattern similar to the older children’s patterns.

From the immune information they gathered, the team developed an Influenza Pediatric Signature (IPS) consisting of a small set of genes that consistently increased or decreased in expression in CD8 T cells from patients with an acute influenza infection. The IPS is able to distinguish acute influenza from ARTIs caused by other pathogens.

“Although this IPS is unlikely to replace clinical virological diagnosis anytime soon, the strength of the IPS score may reflect the severity of disease and provide helpful information post infection,” Wherry said. “It may help focus investigations on the key pathways in this population in the future.”

The researchers’ hope is that by combining the basic science of immune cell gene expression to actual cases seen in a high-volume pediatric ED will identify key pathways involved in host-pathogen interactions and help improve treatments for kids with severe flu symptoms.