Pancreatitis Clinical Mystery Solved

The cause of the pancreatic inflammation- Pancreatitis- plaguing a rural Californian family has remained a medical mystery since it was first described 51 years ago. Now a study by researchers from UC San Francisco and the University of Chicago has solved this clinical mystery: pointing to a novel gene mutation as the cause of the family’s inherited pancreatitis disease.

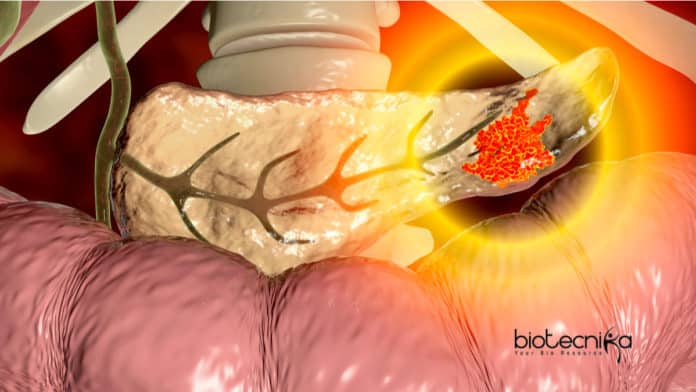

Pancreatitis is a disease where the pancreas becomes inflamed, triggering severe abdominal pain. Long-term pancreatitis inflammation can cause the organ to stop functioning altogether, leading to diabetes, and in many cases, even to pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic Inflammation is most often caused by alcohol abuse, but several forms are also caused by genetic mutations.

In the year 2012, Mark Anderson, MD, Ph.D., who earned his doctorates at UChicago and is now an endocrinologist & professor at the UCSF Diabetes Center, saw a patient in his clinic with diabetes & pancreatitis. The doctor explained that it ran in her patient’s family — in fact, they had been written up in a study for the Annals of Internal Medicine in the year 1968. Scientists at UCSF had documented Seventy-one members of the family — then living in a farming community around

Northern California. Of the 18 people they examined, 6 were officially diagnosed with pancreatitis and another 5 were suspected of having the disease. This particular form of pancreatitis affecting the family was especially severe & struck at a very young age; Kids suffering from it were said to come inside from the fields & collapse onto the floor in pain.At the time, the scientists suspected that it was an autosomal dominant form of the disease where it could be inherited through one mutated gene. There was no way of proving this point back then — before the advent of the genetic sequencing — so this case was closed.

When Anderson and his research colleagues realized their patient’s connections to this classic study, they ordered genetic tests for the patient & several of her family members. Working together with Scott Oakes, MD, a former pathologist at UCSF & cell biologist now on the faculty at the University of Chicago, they screened the family for the 5 known genetic mutations that can cause inherited pancreatitis inflammation disease. None of them actually matched, but a new gene mutation that produces a digestive enzyme called elastase 3B emerged as a possible culprit.

In the laboratory, the scientists used CRISPR-targeted gene editing to engineer mice that had either the normal or the mutated gene version for elastase 3B. Researchers say that the mutated form of the gene actually causes the pancreas to secrete an excess of the enzyme, which damages the pancreas as the enzyme begins to digest itself. After fifty-one years, scientists had an answer for what was really causing the unfortunate family’s misery.

This discovery was published in September in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. Scott Oakes, who calls this as a work of “medical archaeology,” says it is also an opportunity to find new treatments and medications for inherited forms of pancreatitis, a notoriously difficult disease to treat. And short of removing the pancreas — which has the equally problematic side effects of making patients diabetic — or performing a pancreas or islet cell transplant, scientists can mostly just help the patients manage their pain & symptoms.

Oakes added there are a lot of patients who still have what looks like inherited pancreatitis that does not have a genetic diagnosis — maybe some of these have genetic mutations in elastase 3B; So, it has immediate implications not only for this family but potentially other families that have pancreatic inflammation.

Understanding how this gene mutation works could lead to the solutions for more patients as well, Oakes said. New drugs and medications could target the elastase 3B gene with an antibody or molecule that counteracts the extra enzymes produced.

He added the presentation is so dramatic it is possible that elastase 3B might be a good place to intervene in regular, garden-variety pancreatitis inflammation.

Oakes echoed Anderson’s sentiment about the advantages of working on such a problem at institutions like UChicago & University of California San Francisco, where physician-scientists can see patients one day and work in a genetics laboratory the next.

This also reinforces the advantage of seeing patients and running a laboratory: We can let human genetics drive our understanding of this pancreatitis disease,” he added that there are a lot of families like this in the medical literature where we still do not know the genetics. He thinks it is an exciting time now to figure out how to do that.