We have all seen the ugly side of the Zika virus- a harmful virus that can cause devastating brain damage in babies, little did we know that there existed another- a rather helpful side- of the virus as well.

The virus, which arrived in South America from Polynesia around four years ago, is found to be most dangerous in pregnant women- causing microcephaly, an abnormally small head size, and associated neurological problems in the babies of women who were infected while pregnant, as well as a higher rate of miscarriage. The virus does this because, unlike most microbes, Zika can pass from blood into the brain, where it infects and kills stem cells, having severe effects on developing brains.

Now, a new research from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of California San Diego School of Medicine shows that the virus kills brain cancer stem cells, the kind of cells most resistant to standard treatments; hence proving itself highly capable of combating glioblastoma, a deadly form of brain cancer.

“We showed that Zika virus can kill the kind of glioblastoma cells that tend to be resistant to current treatments and lead to death,” said Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine at Washington University School of Medicine and the study’s co-senior author.

Glioblastomas are traditionally treated with surgery, followed by radiation and chemotherapy. However, it is impossible to remove all the cancer without also removing healthy tissue and risking brain damage. So the cancer nearly always comes back. Cancer stem cells cause the recurring tumors. These cells bear strong genetic resemblances to normal stem cells, and can proliferate greatly. Just one cell can regrow an entire tumor.

These Glioblastoma stem cells also resist chemotherapy and radiation. But because they are stem cells, they are vulnerable to Zika. The virus causes an abnormally small head, or microcephaly, by destroying immature neural cells.

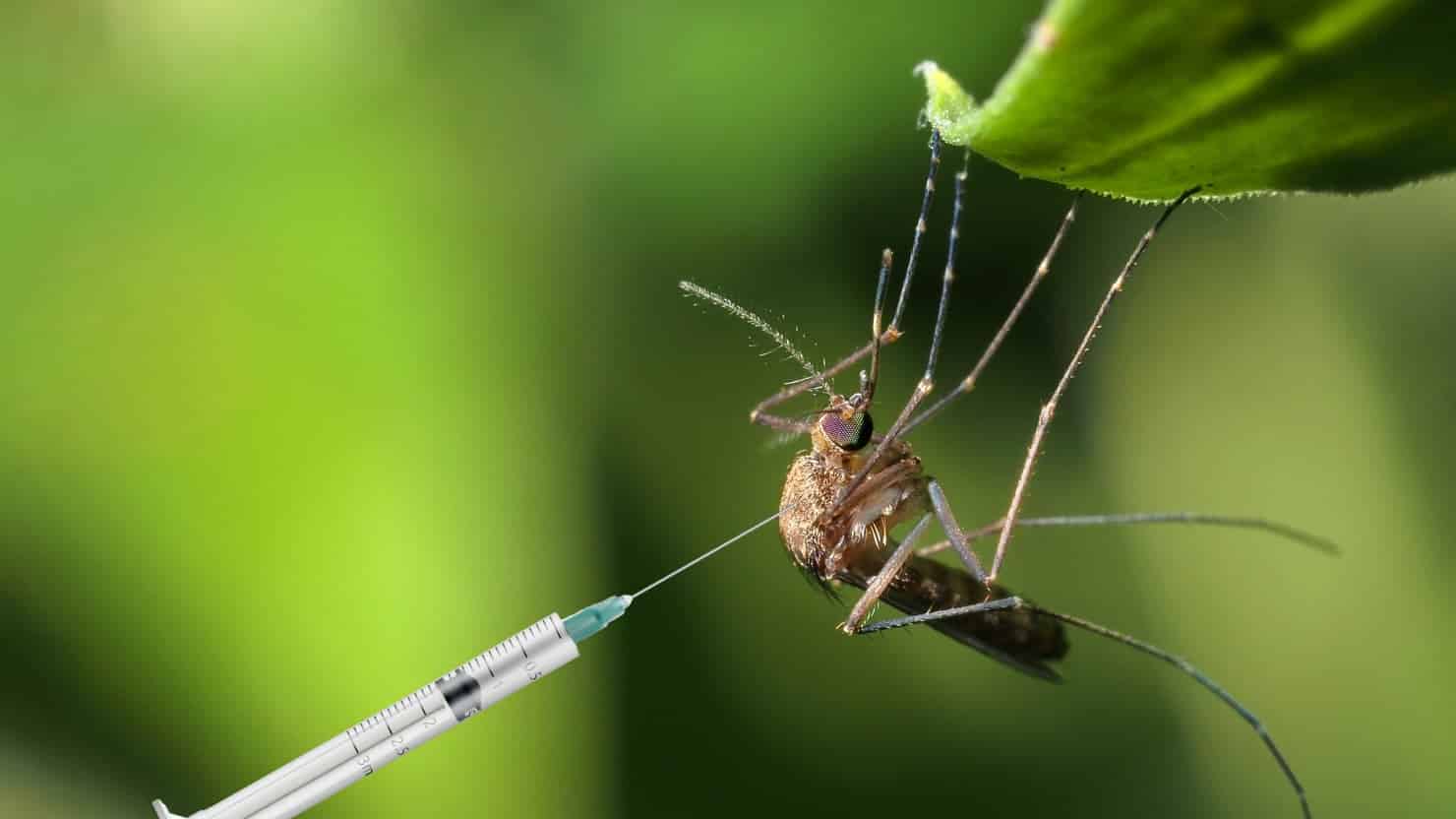

The study authors say a modified Zika virus could be applied after surgery, penetrating to the remaining cancer cells and killing them.

In this laboratory study, researchers introduced ZIKV to glioblastoma tissue samples removed from cancer patients as part of their treatment, as well as to healthy human neural tissue cultures. After seven days, the researchers found that ZIKV had replicated in certain glioblastoma cells and prevented them from multiplying, while the ordinary neural tissue cultures remained largely uninfected.

The researchers also tested mice with glioblastomas, treating an experimental group with a mouse-adapted strain of ZIKV. Mice who received ZIKV survived longer than mice in the control group, and their tumors were significantly smaller than those in the control mice after one week.

“We see Zika one day being used in combination with current therapies to eradicate the whole tumor,” said Chheda, an assistant professor of medicine and of neurology.

If Zika were used in people, it would have to be injected into the brain, most likely during surgery to remove the primary tumor. If introduced through another part of the body, the person’s immune system would sweep it away before it could reach the brain.

The idea of injecting a virus notorious for causing brain damage into people’s brains seems alarming, but Zika may be safer for use in adults because its primary targets – neuroprogenitor cells – are rare in the adult brain. The fetal brain, on the other hand, is loaded with such cells, which is part of the reason why Zika infection before birth produces widespread and severe brain damage, while natural infection in adulthood causes mild symptoms.

“We’re going to introduce additional mutations to sensitize the virus even more to the innate immune response and prevent the infection from spreading,” concluded Diamond, who also is a professor of molecular microbiology, and of pathology and immunology. “Once we add a few more changes, I think it’s going to be impossible for the virus to overcome them and cause disease.”