Alexander Fleming’s original penicillin-producing mould, penicillium sequenced

For the first time, the genome of Alexander Fleming’s penicillin mould has been sequenced and compared with later versions.

Penicillin is a remarkable discovery in the field of medicine. Alexander Fleming is famously known for the discovery of this first antibiotic in 1928. A mould belonging to the genus Penicillium accidentally started growing in a petri dish, produced the first antibiotic.

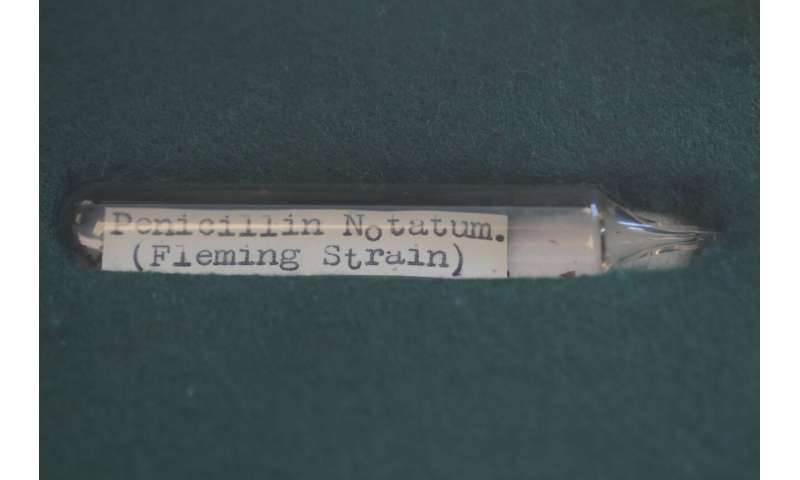

Now, using fifty years old samples that were frozen alive, the genome of the original Flemin

g’s Penicillium is sequenced by a team of researchers from Imperial College London, CABI, and the University of Oxford.The team also compared industrial sample genomes from the US with the genome of Fleming’s mould. The study is published in Scientific Reports. It reveals the minor difference in the penicillin production between the US and the UK strains. This suggests potential new routes for industrial production.

Professor Timothy Barraclough, Imperial College London, said that the team originally planned to use Fleming’s fungus for some different experiments when they realized that, despite the historical significance of the original Penicillium, it was not sequenced.

Industrial production of the antibiotic in the US quickly moved to use mouldy cantaloupes fungus despite Fleming’s mould being famous as the original source of penicillin. After the discovery of penicillin, Penicillium strains producing higher volumes of penicillin were artificially selected.

The team revived Fleming’s original Penicillium frozen samples and re-grew them and extracted the DNA for sequencing. The samples were kept at the culture collection at CABI. The genome of the original Penicillium was compared with two previously sequenced US strains.

Two genes were of particular interest for the researchers: The enzyme encoding genes, used by the fungus in penicillin production, and the genes that regulate the enzymes.

The regulatory genes in both the UK and the US strains had similar genetic code, but there were more copies of regulatory genes in the US strains. The extra regulatory genes in the US strains helped them produce more penicillin.

However, there were differences in the strains isolated in the UK and the US, in the gene code of penicillin producing enzyme. The researchers suggested that this variation infers that wild Penicillium naturally evolved to produce different versions of these enzymes.

Antibiotics are produced by the Penicillium as a defense mechanism against microbes. These moulds are in a constant arms race as the microorganisms evolve paths to evade these defenses. In order to adapt to their local microbes, the US and the UK strains evolved differently.

Micro-organisms evolve and become resistant to present antibiotics. This is a big problem at present times. Although the consequences of the different enzyme sequence for the eventual antibiotic is unknown, the researchers point out the intriguing prospects of ways to modify penicillin production.

Ayush Pathak, the First author of the paper, said that this research could encourage novel solutions to combat resistance to antibiotics. The change in the number of genes in the industrial strains resulted because in the production of penicillin in the industries, the amount produced and the steps involved in the production are the main focus. But there is a possibility that the industrial methods missed out on some penicillin design optimization and Mr. Pathak says that their team can learn from the natural responses to the evolution of antibiotic resistance in their research.

Alexander Fleming’s original penicillin-producing mold, penicillium sequenced

Author: Mayuree Hazarika