Mini DNA Reader For Progressive Development of Anticancer Drugs

Working with nanometers size of DNA is not an easy task. Pulling out a microscope is not enough. Scientists got to be creative to curtail the difficulties they face while working with nanostructure of DNA especially working with single strands. This problem is often faced in Cancer research conducted globally wherein the proposed drugs need to be tested at the nanomolecular level.

Researchers from Japan’s Osaka University have published a study in Scientific Reports Journal that explains how they came up with a really modest solution to the challenge of analyzing anticancer drugs integrated into single strands of DNA.

With nearly half of us prone to developing cancer at some point in our life, the demand for publication and effective treatments has never been more crucial. And while researchers are continuously developing new and improved treatments to kill cancer cells or halt their replication, a limited comprehension of how these drugs work can sometimes make it tough to advance otherwise promising treatments.

One such therapy, trifluridine, is an anticancer drug that gets integrated into DNA since it reproduces. While

similar to thymine, among the four nucleotides that make up DNA adenine. This destabilizes the DNA molecule, leading to cell death gene expression and, ultimately.But where trifluridine becomes integrated into the DNA remains a puzzle because it isn’t distinguished by DNA sequencing methods that are conventional, hampering efforts to comprehend and develop the technologies.

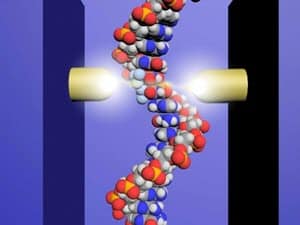

Therefore, the group in Osaka University set about creating a DNA sequencing method that could differentiate the chemical molecules from normal nucleotides in short strands of DNA.

Electric pulses were passed using microscopic probes over a distance of 65,000 times smaller than a grain of sand, just wide enough to match a strand of DNA.

“For the first time, we had the ability to directly discover anticancer drug molecules within the DNA.” explains lead author Takahito Ohshiro

Significantly, the conductance of trifluridine was lower compared to that of those four nucleotides, which displayed conductance values that are divergent. Based on the results inferred, the researchers sequenced DNA strands of up to 21 nucleotides only, locating the exact insertion sites of trifluridine.

“Now that we’ve got the ability to ascertain exactly where the drug is integrated, we could create a better comprehension of the mechanism involved in DNA damage,” says senior writer Masateru Taniguchi. “We hope that this technology will aid in the rapid development of new and more powerful anticancer drugs.”