A Native Brown Fat Protein Key to How the Fat Cells Function

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) and white adipose tissue (WAT) differ in their gene expression signatures, morphologies, and physiological functions. In contrast to WAT, BAT expresses high levels of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and thermogenesis, is rich in mitochondria, and has numerous small lipid droplets compared with the unilocular droplets of WAT.

Because the major function of WAT is to store and release lipid, it is well equipped to adapt to fluctuations in nutrient availability. BAT, on the other hand, is specialized to burn lipids and glucose in response to the need for extra heat, such as reduced ambient temperature or arousal from hibernation. Indeed, with so much focus on WAT and the obesity epidemic, it has only recently been appreciated that adult humans can display cold-activated browning and that relative BAT mass inversely correlates with obesity.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) adaptively transfers energy from glucose and fat into heat by inducing a gene network that uncouples mitochondrial electron transport. However, the innate transcription factors that enable the rapid adaptive response of BAT are unclear.

Now, Salk researchers have discovered how the molecule ERRγ gives this “healthier” brown fat its energy-expending identity, making those cells ready to warm you up when you step into the cold, and potentially offering a new therapeutic target for diseases related to obesity.

“This not only advances our understanding of how the body responds to cold, but could lead to new ways to control the amount of brown fat in the body, which has links to obesity, diabetes and fatty liver disease,” says senior author Ronald Evans, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and holder of Salk’s March of Dimes Chair in Molecular and Developmental Biology.

“We were interested in what maintains brown fat, even when we’re not exposed to cold all the time,” says Maryam Ahmadian, a Salk research associate and first author of the new paper.

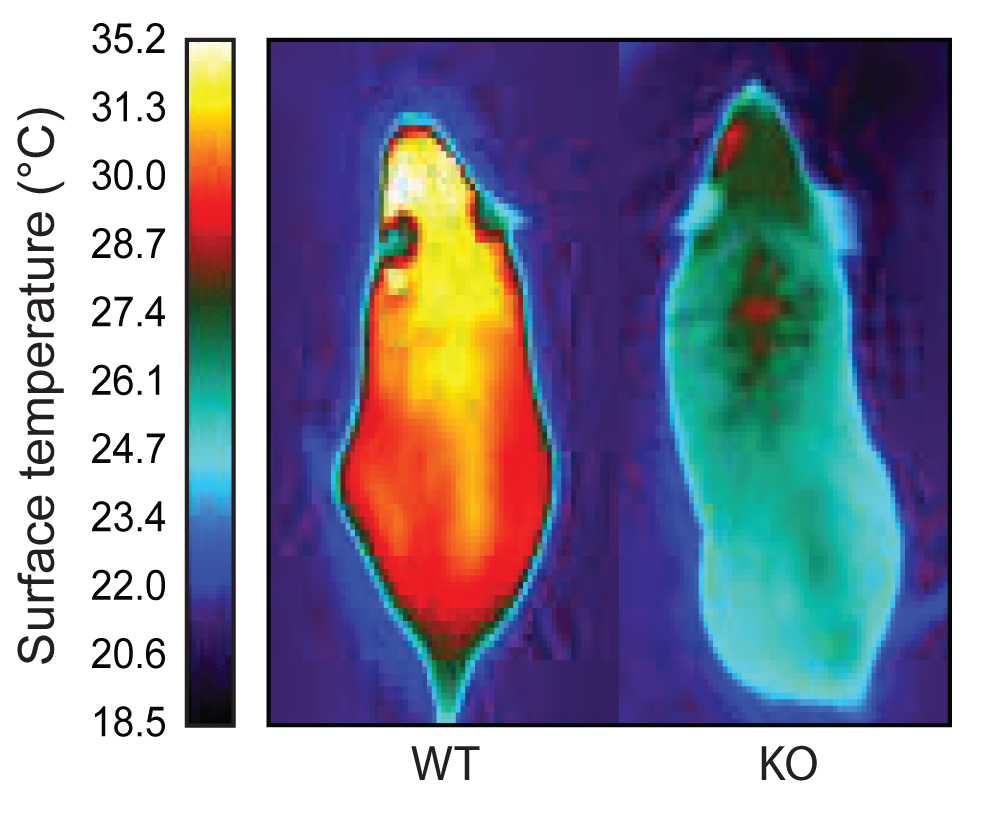

The team found that brown fat cells express the ERRγ gene all the time (not just in response to cold) and that white fat cells do not express the gene at all. And by studying mice lacking the gene for ERRγ (and therefore unable to make the ERRy molecule), the team observed that all brown fat cells resembled white cells in these mice.

Additionally, the animals were unable to maintain their body temperature when exposed to cold temperatures.

The team concluded in a news release that ERRg is “involved in protection against the cold and underpins brown fat identity.” In future studies, the researchers plan to activate ERRg in white fat cells to see if this will shift their identity to be more similar to brown fat cells.