Cancer “Vaccine” Beats Tumours in Mice, All Set for Human Trials

It has recently become apparent that the immune system can cure cancer. In some of these strategies, the antigen targets are pre-identified and therapies are custom-made against these targets. In others, antibodies are used to remove the brakes of the immune system, allowing pre-existing T cells to attack cancer cells.

Similarly, in the most recent attempt to battle cancer, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have designed a “Vaccine”, which, when injected into a tumor triggers the immune system to kill cancer in mice.

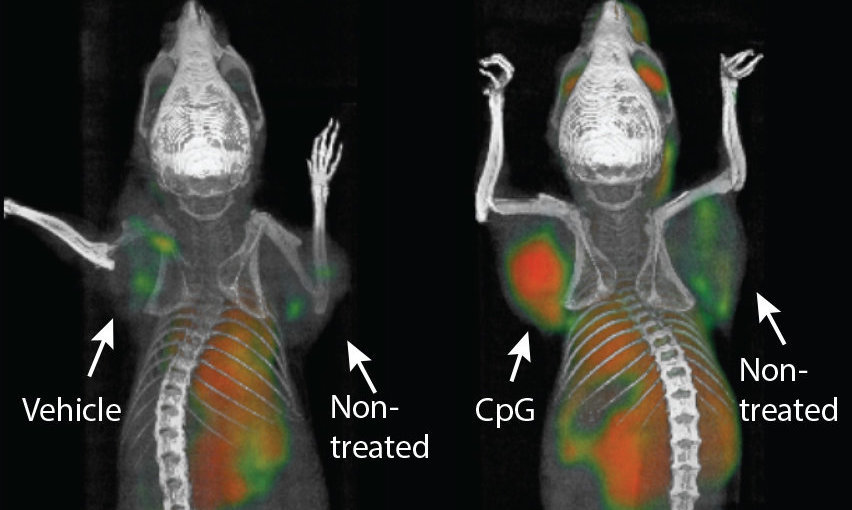

According to this new study, injecting minute amounts of two immune-stimulating agents directly into solid tumors in mice can eliminate all traces of cancer in the animals, including distant, untreated metastases.

“When we use these two agents together, we see the elimination of tumours all over the body,” said senior researcher, oncologist Ronald Levy. “This approach bypasses the need to identify tumour-specific immune targets and doesn’t require wholesale activation of the immune system or customisation of a patient’s immune cells.”

Out of the two immune “agents” used in the study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, one has already been approved for use in humans and the second is currently involved in a lymphoma treatment trial.

In Levy’s two-step cancer vaccine, a short stretch of DNA called a CpG oligonucleotide was first injected into the tumor site.

CpG is something called a Toll-like receptor, a special kind of immune system protein that recognizes invading pathogens. When micrograms of this protein (millionths of a gram) were injected into the mouse tumors, they activated the expression of a receptor called OX40 on nearby T cells that had originally swarmed to the tumor site, but had been rendered inactive.

The second injection contained an antibody that attached to those newly activated OX40 receptors and essentially turned the T cells back “on.” Before their activity was suppressed, those same T cells were primed to respond to the precise antigens produced by the tumor. With a boost from the vaccine, now they were back in action.

Once the process is under way, the scientists report, the tumour-hungry T cells leave the initial site and distribute through the body, attacking any and all other similar tumours they find.

“Our approach uses a one-time application of very small amounts of two agents to stimulate the immune cells only within the tumour itself,” explains Levy. “In the mice, we saw amazing, body-wide effects, including the elimination of tumours all over the animal.”

The team trialled the therapy against several different types of cancers in mice- the first involved 90 animals with lymphoma tumours on both sides of their bodies- in each, only one tumour was treated. The paper details that 87 out of the 90 were cured. The cancer returned in three cases, but went into permanent remission after a second treatment.

Mice carrying breast, colon and melanoma tumours were also treated successfully. Trials were also conducted on mice genetically engineered to develop multiple breast cancers. In many cases treating the first tumour to appear prevented others arising.

“This is a subject that we are still investigating in the animal models where we can track T cells by a variety of different methods that are not possible in humans,” Levy explains.

Although the researchers are optimistic of using this approach to treat all kinds of cancer where T cells have infiltrated the tumor, Levy says that they will start with lymphoma because “it is the cancer of the immune system and most likely to respond to this maneuver.” To that end, a trial is already underway designed to investigate the effectiveness of the technique in 15 patients with low-grade lymphoma.

If it’s effective, the treatment may be used in the future on tumours before they’re surgically extracted to help prevent metastases, or even prevent recurrences of the cancer.

“I don’t think there’s a limit to the type of tumour we could potentially treat, as long as it has been infiltrated by the immune system,” Levy said.