Scientists Call Halt to Cancer Cell Proliferation by Shutting Down Enzymes

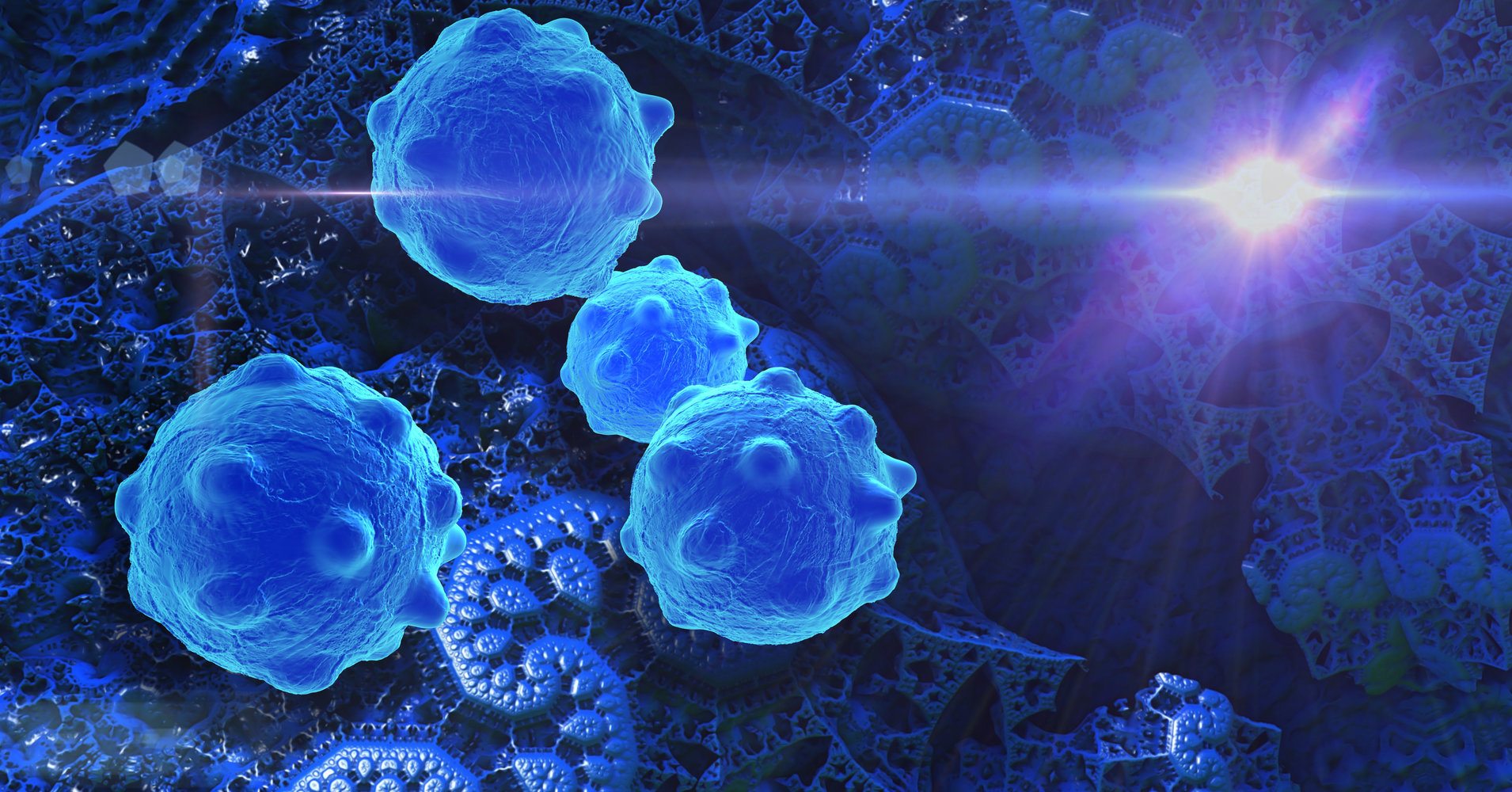

The interactions between proteins and biological membranes are important for drug development, but remain notoriously refractory to structural investigation. Further, turning these proteins or enzymes so as to say, that are important for the survival of growing cells is a promising strategy to fight cancer.

But to be able to shut down only one specific enzyme out of thousands in the body, drugs have to be tailored to exactly fit their target. This has been particularly difficult for membrane proteins, as they only function when incorporated into the membrane lipid bilayer, and often cannot be studied in isolation.

A new study by a collaborative team of scientists at Uppsala University, KTH Royal Institute of Technology and University of Oxford has now been able to demonstrate that shutting down a particular enzyme could curb the growth of cancer cells.

The team achieved this by developing a new technique that shows how drugs inhibit the new cancer target dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH).

The Erik Marklund group at the Department of Chemistry, Uppsala University, has together with the groups of Sir David Lane and Sonia Lain at Karolinska Institutet used computer simulations together

with native mass spectrometry, a technique where a protein is gently removed from its normal environment and accelerated into a vacuum chamber. The researchers used this highly accurate ‘molecular scale’ to see how lipids (the building blocks of the cell membrane) and drugs bind to DHODH.The team also found that DHODH binds a particular kind of lipid present in the cell’s power plant, the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex.

“This means the enzyme might use special lipids to find its correct place on the membrane,” Michael Landreh explains.

“Our simulations show that the enzyme uses a few lipids as anchors in the membrane. When binding to these lipids, a small part of the enzyme folds into an adapter that allows the enzyme to lift its natural substrate out of the membrane. It seems that the drug, since it binds in the same place, takes advantage of the same mechanism,” says Erik Marklund, Uppsala University.

“The study helps to explain why some drugs bind differently to isolated proteins and proteins that are inside cells. By studying the native structures and mechanisms for cancer targets, it may become possible to exploit their most distinct features to design new, more selective therapeutics,” says Sir David Lane, Karolinska Institutet.