Study Reveals Pathway to Targeting Master Regulator of T-Cell Function

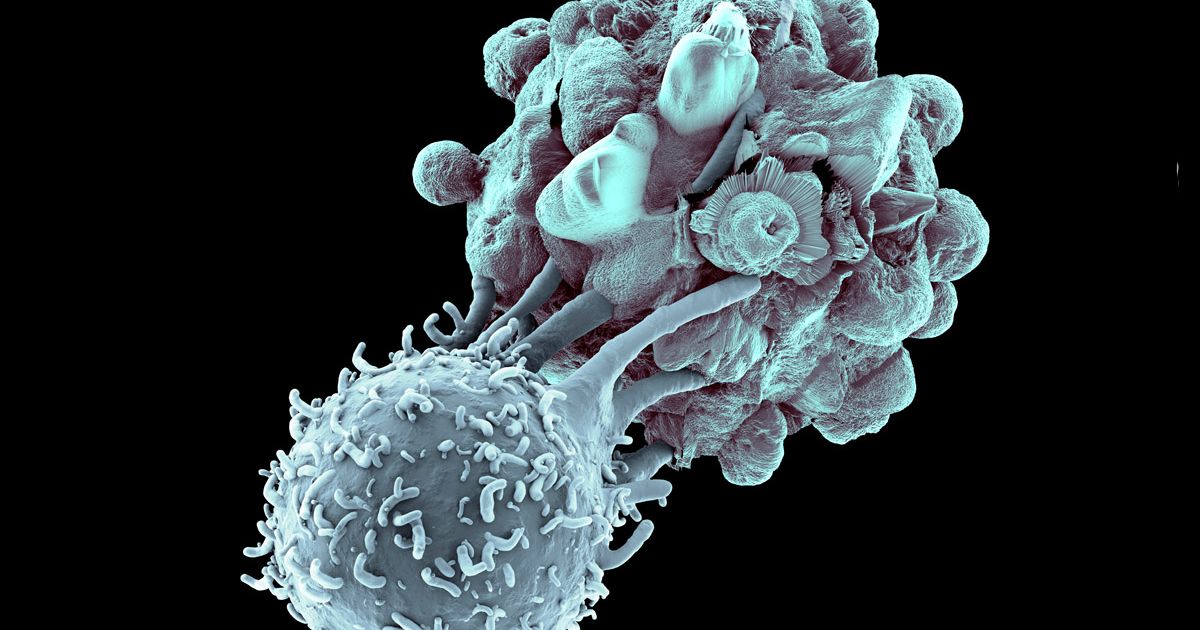

In recent years, substantial advances in T-cell immuno suppressive strategies and their translation to routine clinical practice have revolutionized management and outcomes in autoimmune disease and solid organ transplantation.

More than 80 diseases have been considered to have an autoimmune etiology, such that autoimmune-associated morbidity and mortality rank as third highest in developed countries, after cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

Also, solid organ transplantation has become the therapy of choice for many end-stage organ diseases. Short-term outcomes such as patient and allograft survival at 1 year, acute rejection rates, as well as time course of disease progression and symptom control have steadily improved.

However, despite the use of newer immunosuppressive drug combinations, improvements in long-term allograft survival and complete resolution of autoimmunity remain elusive.

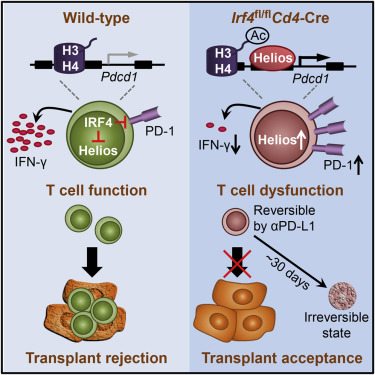

Now, Houston Methodist researchers have cracked a code in T-cells that could make autoimmune diseases and organ transplant rejection a thing of the past. Wenhao Chen and his colleagues have identified a critical switch that controls T-cell function and dysfunction and have discovered a pathway to target it by systematically deleting different molecules in T-cells to check which ones are required for the T-cells to function.

“We found that IRF4 is an essential regulator of T-cell function,” said Chen, who is the corresponding author on this paper. “If we delete IRF4 in T-cells they become dysfunctional. In doing so, you can solve the issue of autoimmunity and have a potential solution for organ transplant rejection. You need them functional, however, to control infection. If we can find an IRF4 inhibitor, then those issues would be solved. That’s big.”

These naïve T-cells produce IRF4 only when needed to fight infections. It’s the activated T-cells armed with IRF4 that are responsible for organ transplant rejection and autoimmunity. These, the team believes, are the ones that are a potential target, thereby leaving other T cells in the immune system still armed against infection.

By inhibiting IRF4 expression for 30 days – the usual timeframe required for transplant patients to remain infection free – the researchers noticed that the T-cells became irreversibly dysfunctional. In practice, this could mean prolonging a patient’s ability to tolerate a transplanted organ.

“How to therapeutically inhibit IRF4 is the Nobel-prize winning question,” Chen said. “If we can find a way to inhibit IRF4 as desired in activated T-cells, then I think most autoimmune diseases and transplant rejection will be solved.”