Sensor Sniffs Out Biomarkers in Meagre Amounts of Body Fluid Samples

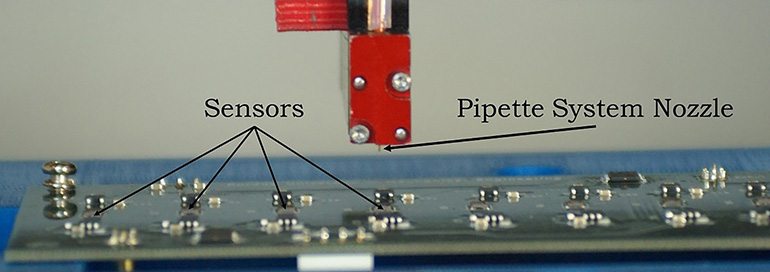

The Purdue University researchers have now designed plate-style microelectromechanical resonator-consisting vibrating sensors to identify biological markers in blood, an advance that could help early-stage detection of diseases and infections.

According to Jeffrey Rhoads, a professor in Purdue’s School of Mechanical Engineering these small vibrating sensors can detect biomarkers using just a drop or two of blood.

“Detecting biomarkers is like trying to find a handful of needles in a large haystack. So we devised a method that divided the large haystack into smaller haystacks,” Rhoads said. “Instead of having a single sensor, it makes more sense to have an array of sensors and do statistical-based detection.”

The sensors use a piezoelectrically actuated resonant microsystem, which when driven by electricity can sense a change in mass. The sensitivity of the resonator increases as the resonant frequency increases, making high-frequency resonators excellent candidates for biomarker detection, Rhoads said. The method also is much faster and less expensive than other types of medical tests.

Rhoads says that one of the first uses for the test could be the early detection of traumatic brain injury in athletes. The sensor-based test can detect minute amounts of proteins, including protein from glial cells, which surround neurons in the brain. The proteins are secreted in relatively high concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of victims of traumatic brain injury.

Research into the effects of repeated head impacts on high school football players has shown changes in brain chemistry and metabolism even in players who have not been diagnosed with concussions, said Eric Nauman, a professor in the School of Mechanical Engineering, Department of Basic Medical Sciences and the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, who is a part of the research team.

Concussions now are diagnosed using a battery of tests, often starting with asking an athlete whether he knows what time it is or where he is. They then move to cognitive tests that grade concussion symptoms along a scale.

Nauman said that while 5 percent to 10 percent of high school football players will be diagnosed with concussions, more than 50 percent of those athletes will experience neurological changes before a concussion is diagnosed. Researchers have learned that a concussion is generally an accumulation of injury and the test they have developed can detect the traumatic brain injury before it becomes symptomatic.

“You do enough damage, you knock out enough systems and eventually you have symptoms,” Nauman said.

“Essentially the idea is that if you can measure anything that passes through the blood-brain barrier from the brain into the blood, it’s a problem because it should stay in the brain,” Nauman said.

The test also is inexpensive so a high school football team could do several mass screenings a season, Rhoads said. Nauman said the Purdue Neurotrauma Group hopes to test high school athletes next fall.

The test also could be used for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, Nauman said. “You can basically look for general neurodegeneration, not just in athletes.”

The researchers believe the test also could be used to detect countless other diseases. They are looking for licensees to use the test to search for other small amounts of protein that are early signs of disease.