A Complex Brain Choreography to Stop You Dead In Your Tracks

Stop lights. Everyone hates them, especially if you’re a runner. Nothing is more jarring than cruising along a run at a solid pace until you realize the world is not with you in your rhythm, and you have to suddenly come to a stop at a busy intersection to wait for the lights to change.

And this split-second decision to change an action once it has already started involves lightning-speed choreography in not just one brain region — as previously thought — but several find researchers at the Johns Hopkins University.

Stopping a planned behavior requires extremely fast choreography between several distinct areas of the brain, the researchers found. If we change our mind about taking that step even a few milliseconds after the original “go” message has been sent to our muscles, we simply can’t stop our feet.

So, in order to find out how our brain works in reality to actually make this happen, researchers led by Susan Courtney, a professor of psychological and brain sciences, monitored the brain activity of 21 people and one monkey as they

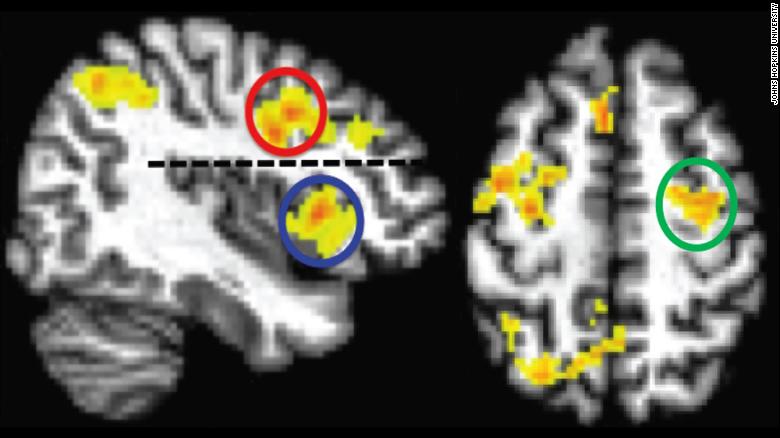

encountered a situation that’s a bit like approaching an intersection when the light turns yellow.The participants were put into an fMRI machine and had them complete a “context-dependent stop signal task.” They were shown colored shapes on a computer screen and asked to either move their eyes or stop their eye movement, based on which color appeared. The eye movement is what’s called a saccade: “a small rapid jerky movement of the eye especially as it jumps from fixation on one point to another.” The researchers measured how quickly the participants could keep going as planned or halt their eye movements.

The study found that stopping an action required three key brain areas to communicate with eight other areas. The team also found that all the communication had to occur within about one-tenth of a second of when a participant saw the cue not to move their eye. After that, a signal has already been sent to the eye muscles and there is no way to stop it, Courtney says.

Those who received the stop signal 100 milliseconds after the circle appeared succeeded in stopping their eye movement more than 75% of the time. But when the signal occurred after 200 milliseconds, the success rate dropped to 50%, illustrating the difficulty of abandoning an action.

By observing brain activity in humans and a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), the team found that successful stopping required coordinated action of the premotor cortex and two areas of the prefrontal cortex. Understanding how people stop or fail to stop actions could help to explain addictive behaviour, the authors say.

“We know people with damage to these parts of the brain have trouble changing plans or inhibiting actions,” she said. “We know as we age, our brain slows down and it takes us longer to find words or to try to make these split-second plan changes. It could be part of the reason why old people fall.”

Knowing more about how the brain can stop an intended activity could also be revealing for those dealing with addictions, Courtney said.

“We think there are similar processes in “should I do this” and “can I turn off that thought about the drink,” Courtney said. “The sooner I can turn off the plan to drink, the less likely I’ll carry out the plan. It’s very relevant.”

“The main thing is to pause for half a second and re-evaluate before you start your action plan. You don’t have to sit and ruminate, necessarily, but that half a second before you have an impulsive decision to do something that you’ll later regret can be very effective.”

In other words: As important as it is to do something quickly, don’t initiate movement until you’re confident you’re making the right decision.