Study Exonerates “Gatekeeper” Neurotransmitters In Pain Transmission

During the 1960s, neuroscientists Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall proposed an influential new theory of pain. At the time, researchers were struggling to explain the phenomenon. Some believed that specific nerve fibres carry pain signals up into the brain, while others argued that the pain signals are transmitted by intense firing of non-specific fibres.

Melzack and Wall’s Gate Control Theory stated that inhibitory neurons in the spinal cord control the relay of pain signals into the brain. Despite having some holes in it, the theory provided a revolutionary new framework for understanding the neural basis of pain, and ushered in the modern era of pain research. Now, almost exactly 50 years after the publication of Melzack and Wall’s theory, researchers at the North Carolina University, raise the possibility that drugs could be developed targeting itching, but not pain, or vice versa, and that neurotransmitters play no role in pain transmission.

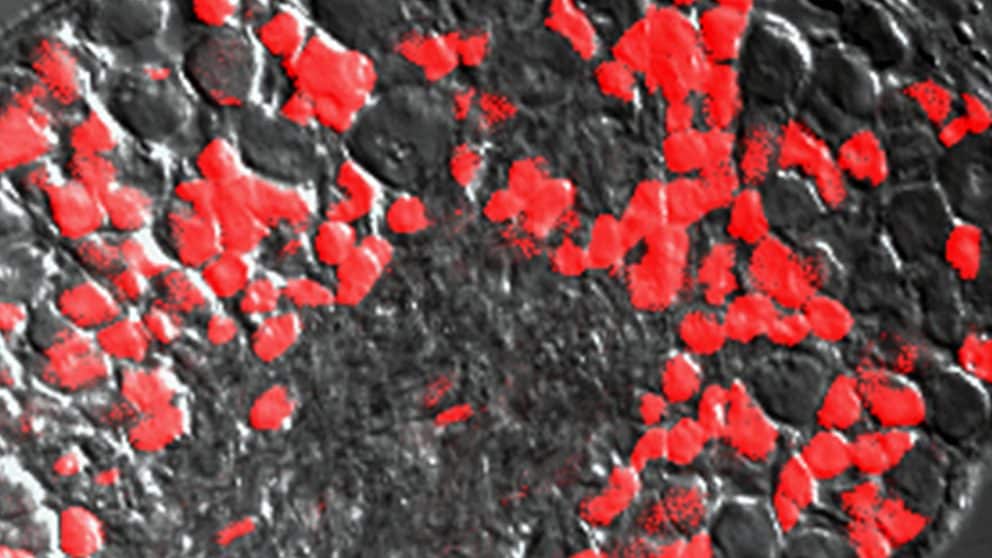

Ever since the discovery of distinct sets of neurons responsible for itch and pain1, numerous studies have been carried out to define and characterize the neurotransmitters responsible for itch and pain. Recent advances in the itch field have identified at least two major neurotransmitters responsible for the perception of itch, gastrin releasing peptide (GRP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP).

The expression pattern and location of these neurotransmitters within the neural itch circuitry has been the source of contention in recent years. Recent studies have implicated BNP as the primary neurotransmitter responsible for itch. BNP, a product of the gene Nppb, is a small peptide hormone that acts on the Npra-receptors within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord2. Studies have reported a loss of scratching response in mice lacking Npraexpressing interneurons in the spinal cord under conditions that would normally induce itch, such as exposure to common pruritogens like histamine and chloroquine.

On the contrary, some studies suggest that GRP is the primary neurotransmitter employed by itch sensory neurons and therefore argue against the BNP-Npra pathway. While many studies have investigated the role of BNP as a primary neurotransmitter involved in itch sensation, very few have been devoted to resolving the potential involvement of BNP in pain sensation.

“For us, it’s very important to understand the neural circuits or pathways so that we can develop therapies specifically for pain or itch, instead of targeting it as a whole system,” says Santosh Mishra, assistant professor of neuroscience in NC State’s College of Veterinary Medicine and the corresponding author of a paper on the topic. “This work shines a light on these different pathways for pain and itch.”

During the course of their investigation, researchers looked at whether BNP played a role in transmitting acute, inflammatory or neuropathic pain in mice. Results were the same for regular mice and those that lacked the BNP gene. “That means BNP was not involved for any of these distinct types of pain,” Mishra says. “We know that if we target BNP, we won’t be inhibiting pain; we’ll be inhibiting itch.”

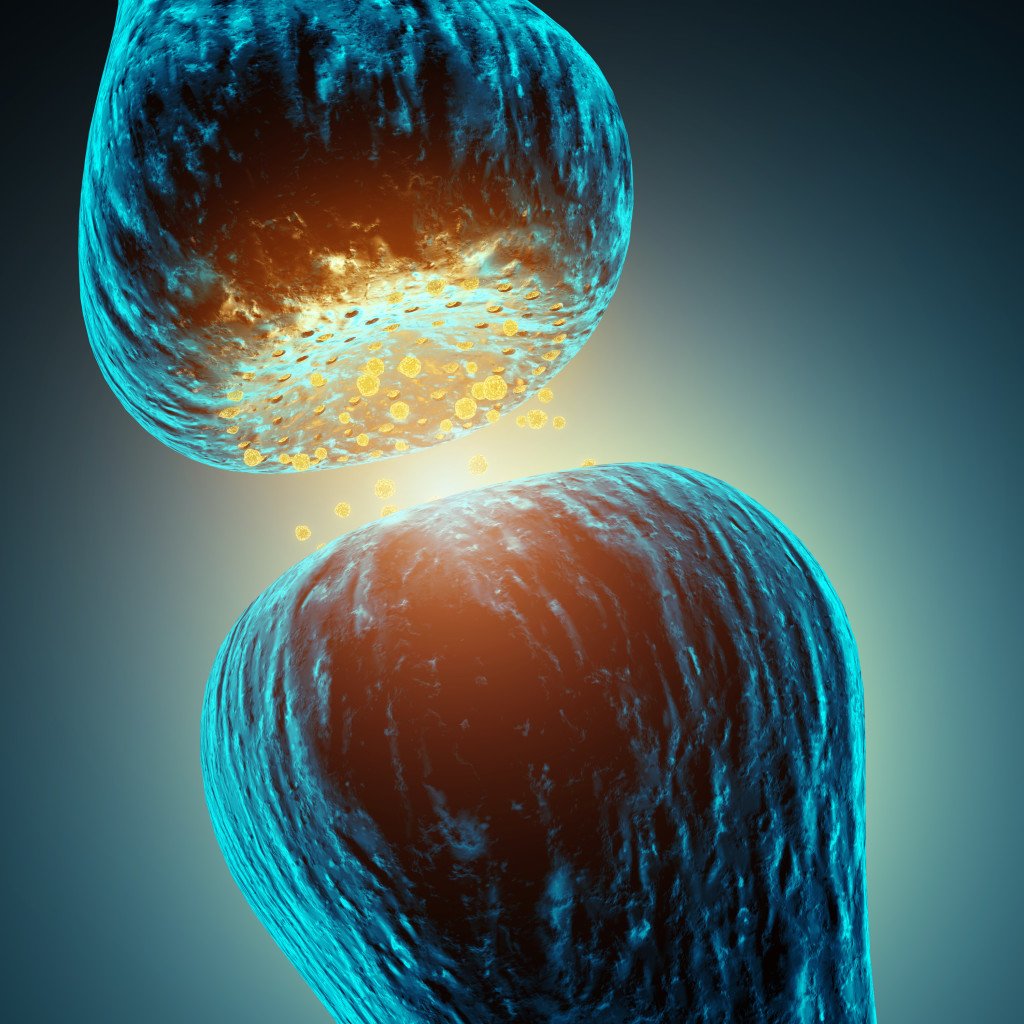

Pain or itching sensations begin when a nerve cell on the surface of the body reacts to a stimulus, starting a chain reaction that moves from cell to cell. The neural pathway takes the message to the spinal cord, which is connected to the brain. The brain interprets the signals from the nerves, creating the sensations of pain and itching.

“If we know how these sensations are transmitted, we can design specific drugs or therapies to block the neurotransmitters, block the receptors for the neurotransmitters or reduce the degree to which those neurotransmitters work,” Mishra says. “I call these the gatekeepers because they are sitting in between the skin and the central nervous system.”

The goal is to develop treatments that interrupt the pain or itch signals closer to the source.

“If we can block the sensation at the peripheral level, in the skin, that is a much friendlier way than to try to target the sensation once it reaches the brain,” Mishra says. “We know the importance of pain management. Studying itching sensations is a relatively new field, but if we look at the number of diseases where itch is a major symptom, it includes not only atopic dermatitis but also nervous system disorders such as multiple sclerosis, as well as infection and end stage kidney disease. This work is an initial step in gaining a better understanding.”