First Evidence of the Body’s Waste System in Human Brain

How does the brain rid itself of waste products?

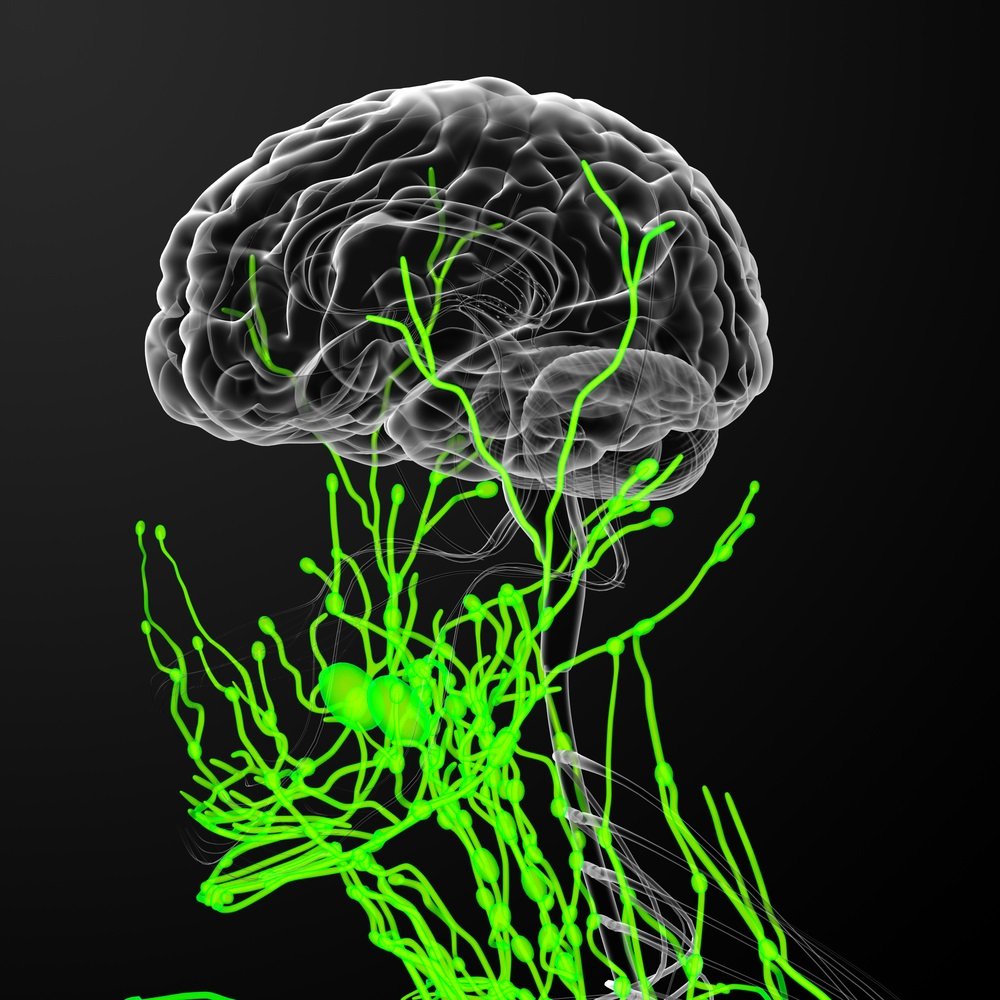

Other organs in the body achieve this via a system called the lymphatic system. A network of lymphatic vessels extends throughout the body in a pattern similar to that of blood vessels. Waste products from cells, plus bacteria, viruses and excess fluids drain out of the body’s tissues into lymphatic vessels, which transfer them to the bloodstream.

Blood vessels then carry the waste products to the kidneys, which filter them out for excretion. Lymphatic vessels are also a highway for circulation of white blood cells, which fight infections, and are therefore an important part of the immune system.

Unlike other organs, the brain does not contain lymphatic vessels. So how does it remove waste? Some of the brain’s waste products enter the fluid that bathes and protects the brain – the cerebrospinal fluid – before being disposed of via the bloodstream.

However, researchers at the at the National Institutes of Health, by scanning the brains of healthy volunteers, have now uncovered the first evidence that our brains may drain some waste out through lymphatic vessels, the body’s sewer system.

Along with researchers from the National Cancer Institute in the US, the research team headed by Daniel S Reich, from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) discovered lymphatic vessels in the dura, the leathery outer coating of the brain.

The team used MRI to scan the brains of five healthy volunteers who had been injected with gadobutrol, a magnetic dye typically used to noninvasively visualize brain blood vessels damaged by disease.

When first looking at the MRI images, the dura lit up brightly and no lymphatic vessels were seen. However, when the scanner was turned differently, the blood vessels disappeared, allowing the researchers to see that the dura also contained smaller but equally bright spots and lines which they suspected were lymph vessels. These results suggested that the dye may have leaked out of the blood vessels, flowed through the dura and into neighboring lymphatic vessels.

A second round of tests where subjects were injected with a larger-molecule dye, incapable of leaking out of blood vessels, revealed only the blood vessels and no lympathic vessels, confirming their suspicions.

Evidence of lymphatic vessels was also found in autopsied human brain tissue and in brain scan of nonhuman primates. This suggests lymphatic vessels may be common in mammals.

“These results could fundamentally change the way we think about how the brain and immune system inter-relate,” said Walter J. Koroshetz, M.D., NINDS director.

Dr. Reich’s team plans to investigate whether the lymphatic system works differently in patients who have multiple sclerosis or other neuroinflammatory disorders.

“For years we knew how fluid entered the brain. Now we may finally see that, like other organs in the body, brain fluid can drain out through the lymphatic system,” said Dr. Reich.