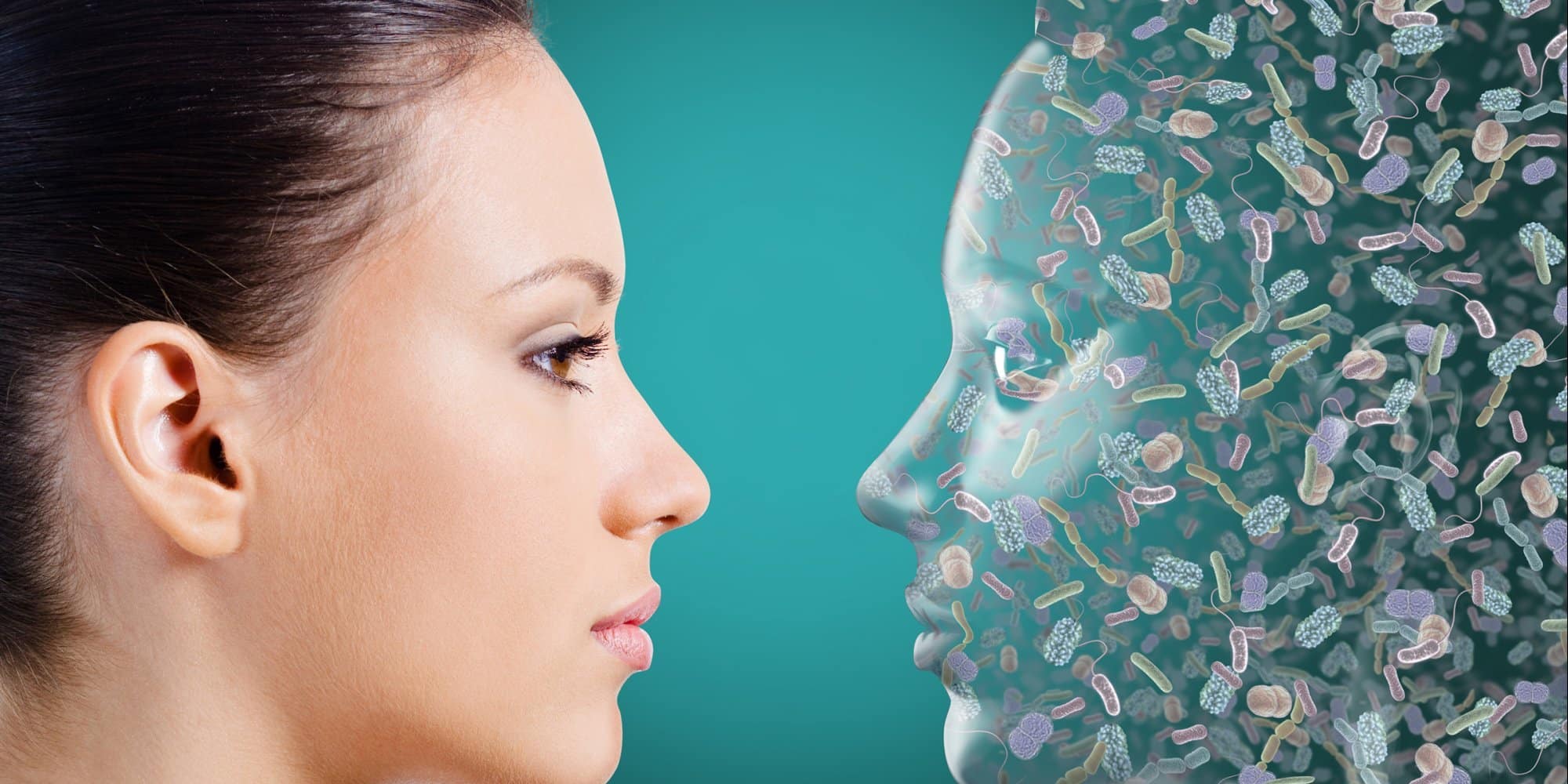

From bacteria to viruses, mites to fungi, our bodies are literally riddled with life. Surprise, surprise.

But what’s most shocking of all is that almost all of these bacteria are relatively unknown.

A dizzying number of microbes call the human body home, this small ecosystem features bacteria on our skin, in our mouths, in our guts, and nearly every corner of our bodies, and they perform crucial tasks that help keep us alive.

Understanding this microbiome is key for doctors and scientists looking to improve human health. Scientists thought they understood most of the microbiome’s mysteries, but new research from Stanford suggests they’re almost completely in the dark.

The discovery was initially made by accident, as a team investigated less invasive ways to predict whether a patient’s body would reject a transplanted organ. Rather than the wholly unpleasant experience of having a tissue biopsy taken, the researchers were studying whether a simple blood sample would suffice. Essentially, the idea was that if they found fragments of the organ donor’s DNA circulating in a patient’s blood, it was a good indication that the body was rejecting the transplant.

The team collected samples from 156 people undergoing organ transplants, and found they

could identify DNA from the patient, from the organ donor, and from the bacteria living inside the patient’s body. But they found something strange: In each case, 99 percent of the DNA they collected failed to match anything in their database, meaning it was completely unknown to science.The team then set about categorizing that pile of unknown DNA, and found that most of it belonged to a general group known as proteobacteria, which counts E. coli and Salmonella among its ranks, along with many, many others. On the virus side of things, the team found a huge amount of previously unknown members of the torque teno family, including an entirely new group that doesn’t quite fit current descriptions.

“We found the gamut,” says Stephen Quake, senior author of the study. “We found things that are related to things people have seen before, we found things that are divergent, and we found things that are completely novel. I’d say it’s not that baffling in some respects because the lens that people examined the microbial universe was one that was very biased.”

“We’ve doubled the number of known viruses in that family through this work. We’ve now found a whole new class of human-infecting ones that are closer to the animal class than to the previously known human ones, so quite divergent on the evolutionary scale.”

“I’d say it’s not that baffling in some respects because the lens that people examined the microbial universe was one that was very biased,” Quake said, in the sense that narrow studies often miss the bigger picture. For one thing, researchers tend to go deep in the microbiome in only one part of the body, such as the gut or skin, at a time. Blood samples, in contrast, “go deeply everywhere at the same time.”

For another, researchers often focus their attention on just a few interesting microbes, “and people just don’t look at what the remaining things are,” Kowarsky said. “There probably are some interesting, novel things there, but it’s not relevant to the experiment people want to do at that time.”

It was by looking at blood samples in an unbiased way, Quake said, that led to the new results and a new appreciation of just how diverse the human microbiome is.

Going forward, Quake said, the lab hopes to study the microbiomes of other organisms to see what’s there. “There’s all kinds of viruses that jump from other species into humans, a sort of spillover effect, and one of the dreams here is to discover new viruses that might ultimately become human pandemics.” Understanding what those viruses are could help doctors manage and track outbreaks, he said.