The Brain Re-Maps Its Visual Areas To Process Language In Blind People

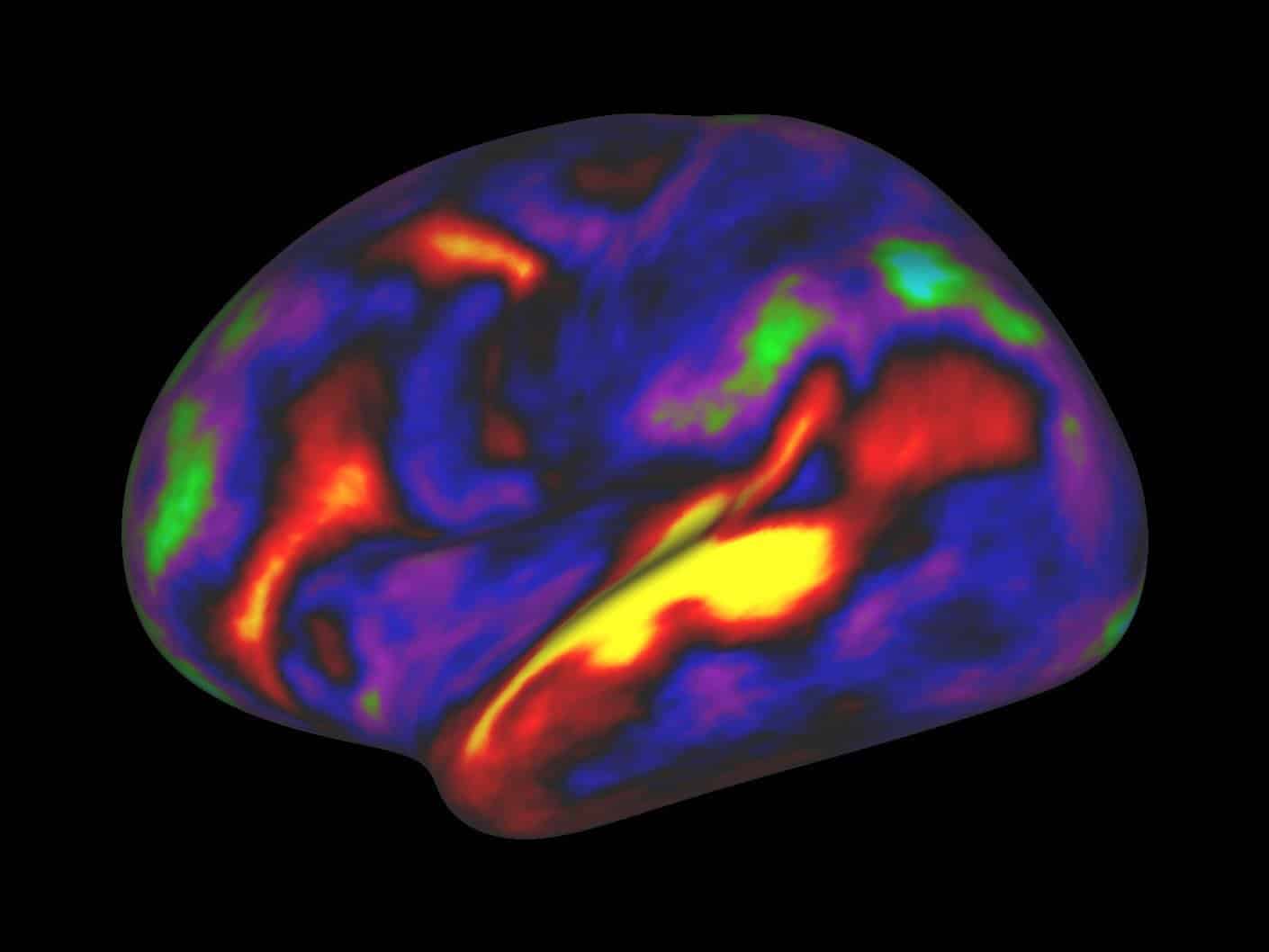

In a new study that could have important implications for neurologists’ understanding of “plasticity”, or how the brain adapts to experience, scientists at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium have found that parts of the brain once thought to be primarily devoted to processing vision can be recruited by blind people to process speech.

The finding builds on previous research showing that the parts of the brain responsible for vision can learn to process other kinds of information, including touch and sound, in people who are blind.

In the course of the study, the lead scientist Olivier Collignon and his team exposed groups of sighted and blind volunteers to three clips from an audio book while being scanned using magnetoencephalography (MEG).

One recording was clear and easy to understand; another was distorted but still intelligible; and the third was modified so as to be completely incomprehensible. Both groups showed activity in the brain’s auditory cortex, a region that processes sounds, while listening to the clips. But the volunteers who were blind showed activity in the visual cortex, too.

The researchers say the blind volunteers also appeared to have neurons

in their visual cortex that fired in sync with speech in the recording – but only when the clip was intelligible which suggests that these cells are vital for understanding language.The discovery highlights how malleable our brains are, says Collignon, but he thinks there may be a limit to this. It’s unlikely that any part of the brain can eventually learn any function, he says. Instead, there may be a set of rules, laid down in our genes, which brain regions can follow.

There is also a visual aspect to understanding language, says Collignon. It is easier to understand what someone is saying if you are looking at them and watching the movements of their lips, for instance. “Brain regions are more dedicated to a function than to an input,” he says.

Collignon hopes his research will aid the development of treatments to restore vision. By better understanding how the brain can adapt to new inputs, researchers may be able to predict whether such treatments can rewire the recipient’s brain to allow them to see.