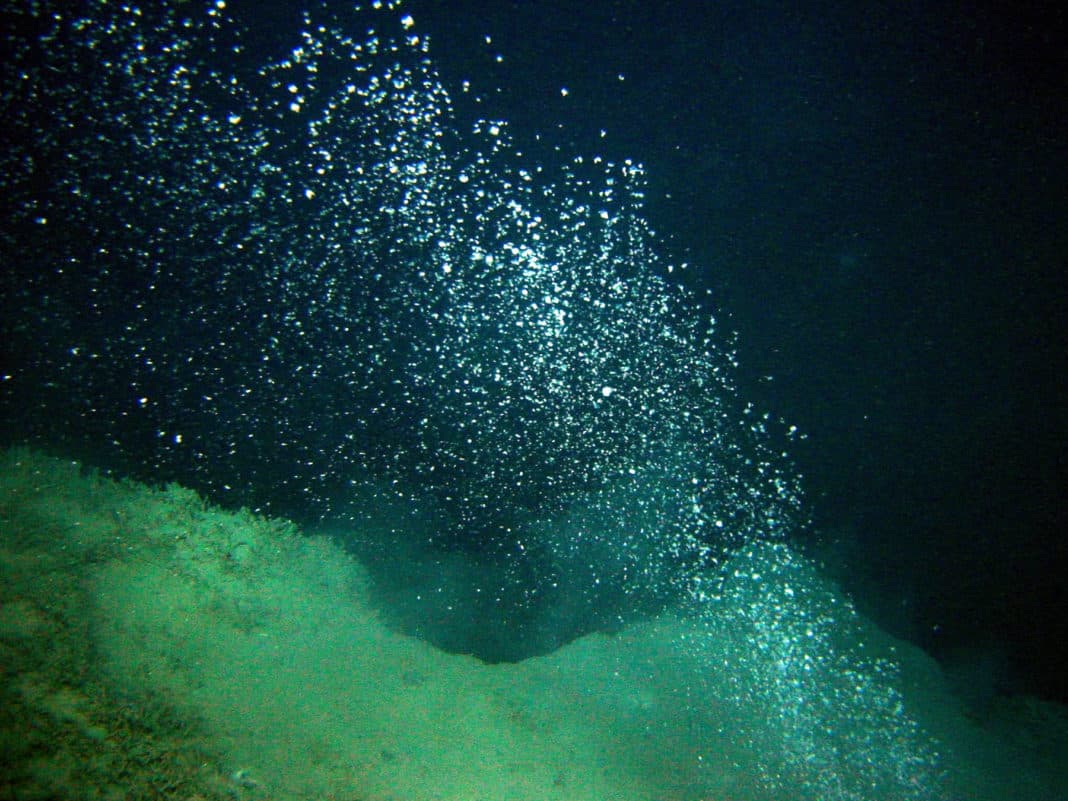

Tiny bacteria lurking in a lake half a mile beneath Antarctica’s icy surface may mitigate the release of this greenhouse gas into the atmosphere as ice sheets retreat.

An international and interdisciplinary team of scientists, in 2013, drilled 800 meters (2,600 feet) into the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, where they reached Lake Whillans. The researchers collected samples of water and sediments that had been isolated from the atmosphere for many thousands of years.

Their analysis of the samples, now published in Nature Geoscience, revealed bacteria that digest methane. The microbes were in the upper lake sediment, indicating they prevent the greenhouse gas from entering the water—ensuring this Earth-heating compound is then unable to reach the ocean and escape into the atmosphere.

“Not only is this important for the global climate, but methane oxidation could be a widespread means of life for microbes in the deep, permanently cold biosphere beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet,” lead author Alexander Michaud, from Montana State University, said in a statement.

Methane is far more potent than carbon dioxide; although methane, made of

hydrogen and oxygen, eventually decays into carbon dioxide, its warming effects are much stronger during the decades before that happens.According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the planet-warming effect of methane is 86 times greater than that of carbon dioxide.

Scientists believe a major methane reservoir lies beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet, in addition to the huge amount held within the permanently frozen ground of the Arctic permafrost. Climate scientists are concerned that as global temperatures increase, methane released from warmed permafrost will cause additional warming—potentially resulting in runaway climate change. The bacteria that eat this chemical could be preventing its release into the atmosphere, limiting global warming in the process.

The study says that consuming methane is a matter of survival for these bacteria. Cut off from heat and sunlight, they turn to this gas for energy. “Bacterial oxidation consumes [more than] 99 percent of the methane and represents a significant methane sink,” the scientific team wrote.

“There’s been a lot of concern about the amount of methane that’s beneath these ice sheets because we don’t know exactly what’s going to happen to it,” said Brent Christner, a University of Florida microbiologist and co-author on the study.

The study found that Lake Whillans contains large amounts of methane. Melting Antarctic ice sheets may release the trapped gases stored in these underground lake reservoirs, Christner said. Researchers have estimated that over 10^14 cubic meters of methane, enough gas to fill more than a billion hot air balloons, is stored beneath Antarctic ice, ready to be released under the right conditions.

Understanding the vast systems of lakes and rivers beneath the Antarctic ice sheet is important to climate science. But these ecologies are still largely unexplored, making it difficult to predict how much methane they might release in the future. “It took more than a decade of scientific and logistical planning to collect the first clean samples from an Antarctic subglacial environment, but the results have transformed the way we view the Antarctic continent,” study co-author John Priscu, a polar scientist and professor in Montana State University’s Department of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences said in a statement.

Concluding, the team wrote, “The bacterial conversion of [methane] to [carbon dioxide] beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet reduces the warming potential of subglacial gases that may be released to downstream ice sheet margin environments and to the atmosphere during episodes of ice sheet retreat.”