Biochemical Markers Indicative of Osteoarthritis Identified Using Nanotech

Hyaluronan (or hyaluronic acid, HA) is widely distributed throughout mammalian cells and tissues. Both the abundance and size distribution of HA in biological fluids are recognized as robust indicators of various pathologies and disease progressions.

While the molecular weight (MW) of naturally occurring HA is typically in the range of 105–107 Da (~250–25,000 disaccharide units, each ~1 nm in length), its size within this range is a critical determinant of the molecule’s function in vivo. For example, high-MW HA (>1000 kDa) is highly viscous and appears to display anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties; whereas, low-MW HA (generally <500 kDa) can induce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages.

Unfortunately, current technologies for HA detection and size differentiation have significant limitations. Now, investigators from Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center have been able to incorporate nanotechnology into the detection and measurement of HA as a biomarker indicative of osteoarthritis and many other inflammatory diseases.

“Our results established a new, quantitative method for the assessment of a significant molecular biomarker that bridges a gap in the conventional technology,” said lead author Adam R. Hall, Ph.D., assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Wake Forest School of Medicine, part of Wake Forest Baptist.

“The sensitivity, speed and small sample requirements of this approach make it attractive as the basis for a powerful analytic tool with distinct advantages over current assessment technologies.”

In the study, Hall, Rahbar and their team first employed synthetic HA polymers to validate the measurement approach. They then used the platform to determine the size distribution of as little as 10 nanograms (one-billionth of a gram) of HA extracted from the synovial fluid of a horse model of osteoarthritis.

A microchip with a single hole, or pore, a few nanometers wide- about 5,000 times smaller than a human hair- was used. Only individual molecules can pass through the opening and researchers measured their size one-by-one.

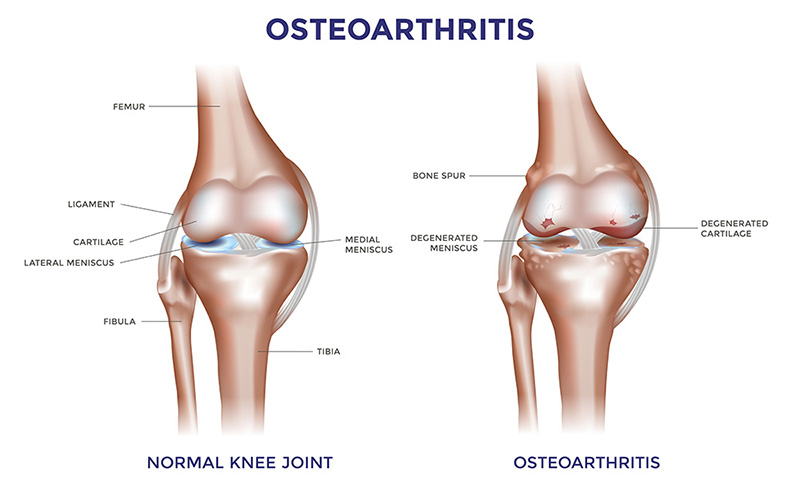

Because the molecole’s size distribution changes over time in osteoarthritis, this technology could help better assess disease progression, Hall said.

“By using a minimally invasive procedure to extract a tiny amount of fluid – in this case synovial fluid from the knee – we may be able to identify the disease or determine how far it has progressed, which is valuable information for doctors in determining appropriate treatments,” he said.

Hall, Rahbar and their team hope to conduct their next study in humans, and then extend the technology with other diseases where HA and similar molecules play a role, including traumatic injuries and cancer.